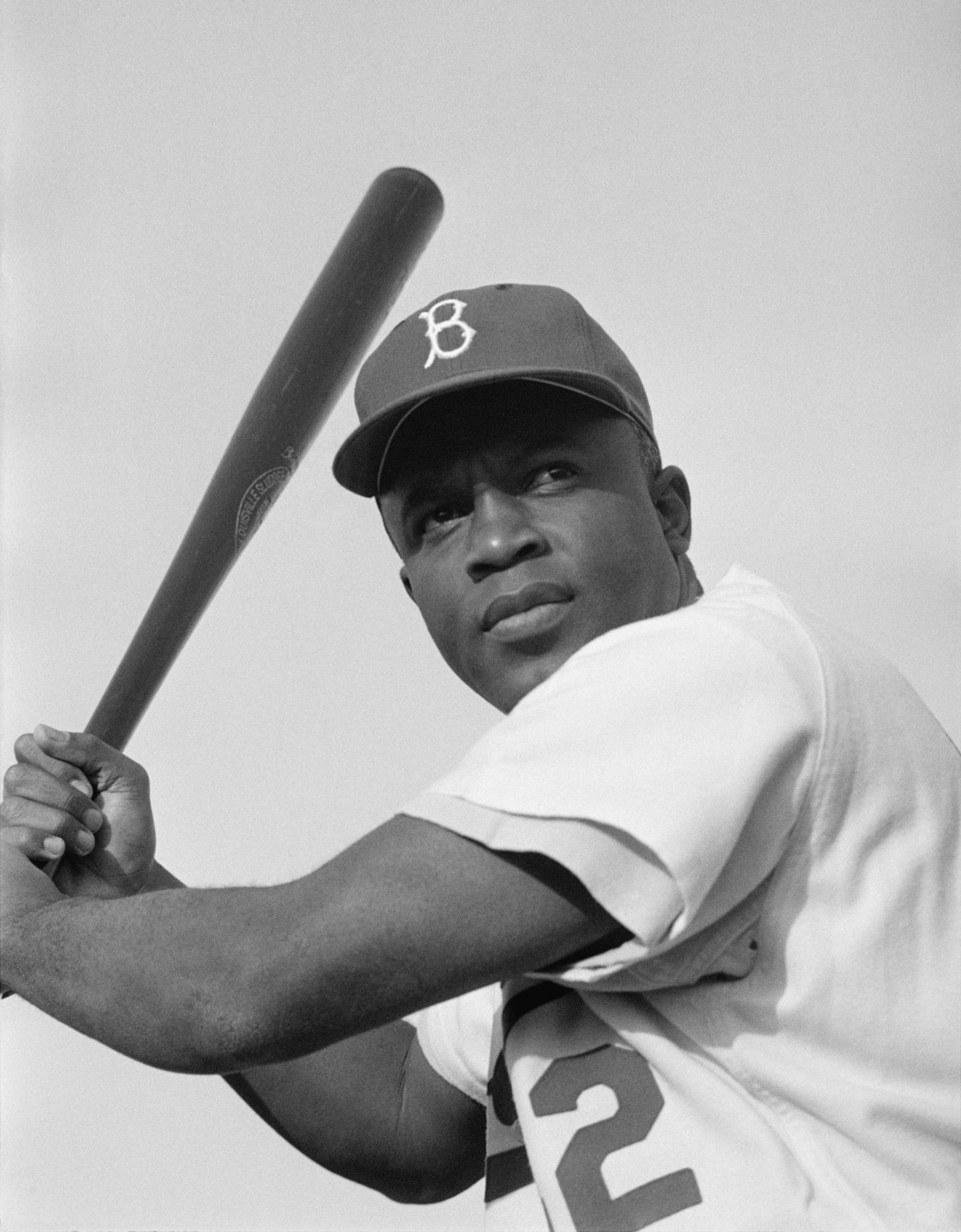

Honoring the legacy of Jackie Robinson

April 15th is the 75th anniversary of his breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball

This week marks the 75th anniversary of Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball in the modern era.

Robinson became the first African American to play modern Major League Baseball when he started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947.

This remarkable milestone is a good time to take a look at the groundbreaking history made by the baseball legend and civil rights champion.

First it is important to note that Robinson was not the first African American to play in the major leagues.

In 1884, Moses Fleetwood Walker played for the Toledo Blue Stockings as catcher. The team was part of the American Association, one of three major leagues of its day. Baseball maintained segregation for many decades after this and Robinson became the first player to end this segregation in April 1947.

According to the study by the Society for American Baseball Research, William Edward White was the first African American baseball player in the major leagues.

However White passed as a white man and self-identified as such. Walker was the first to be open about his black heritage, and to face the racial bigotry so prevalent in the late 19th century United States. Walker played just one season, 42 games total, for Toledo before injuries resulted in his release.

Walker played in the minor leagues until 1889 and was the last African American to participate on the major league level before Robinson broke baseball’s color line in 1947. After his baseball career, Walker became a successful businessman and inventor. As an advocate of Black nationalism, he also jointly edited a newspaper, The Equator, with his brother. Walker also published a book, Our Home Colony (1908), to explore ideas about emigrating back to Africa. He died in 1924 at the age of 67.

When Jackie Robinson stepped onto Ebbets Field in Brooklyn at the age of 28, it was a remarkable moment in the history of major league baseball and for racial equality in the United States. Robinson had broken the color barrier in a sport that had been segregated for more than 50 years.

Robinson’s history-making journey is worth noting.

Jack Roosevelt Robinson was born on January 31, 1919, in Cairo, Georgia, a small town not far from the Florida-Georgia line and reared in Pasadena California.

Robinson became an outstanding all-around athlete at Pasadena Junior College and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where he excelled in football, basketball, and track as well as baseball. He withdrew from UCLA in his third year to help his mother care for the family.

In 1942 he entered the U.S. Army and attended officer candidate school; he was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1943. Robinson faced court-martial in 1944 for refusing to follow an order that he sit at the back of a military bus. The charges against Robinson were dismissed, and he received an honorable discharge from the military. Upon leaving the army, he played baseball with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League, where he drew the attention of Branch Rickey, the president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Rickey had been planning an attempt to integrate baseball and was looking for the right candidate. Robinson’s skills on the field, his integrity, and his family-oriented lifestyle appealed to Rickey. Rickey’s main fear was whether Robinson would be unable to withstand the racist abuse without responding in a way that would hurt integration’s chances for success. During a legendary meeting Rickey shouted insults at Robinson, to see if Robinson could accept taunts without incident. On October 23, 1945, Rickey signed Robinson to play on a Dodger farm team, the Montreal Royals of the International League.

Robinson led that league in batting average in 1946 and was brought up to play for Brooklyn in 1947. He was an immediate success.

He led the National League in stolen bases and was chosen Rookie of the Year. In 1949 he won the batting championship with a .342 average and was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player (MVP).

Robinson succeeded on the field while enduring fans hurling bottles and racial slurs at him. Some Dodger teammates openly protested against having to play with an African American, while players on opposing teams deliberately pitched balls at Robinson’s head and spiked him with their shoes in deliberately rough slides into bases.

One of the worst incidents happened when the Philadelphia Phillies came to Ebbets Field to face the Dodgers in Brooklyn in 1947, his rookie year. The insults and the taunts were not only from fans but from Phillies players. Robinson later wrote that he considered giving up and tearing into the Phillies’ dugout.

Robinson did have some allies. When players on the St. Louis Cardinals team threatened to strike if Robinson took the field, commissioner Ford Frick quashed the strike, countering that any player who did so would be suspended from baseball. Dodger captain Pee Wee Reese left his position on the field and put an arm around Robinson in a show of solidarity when fan heckling became intolerable, and the two men became lifelong friends.

Through death threats, and Jim Crow laws that forbade a Black player to stay in hotels or eat in restaurants with the rest of his team, he remained undeterred.

Robinson had a stellar baseball career. His lifetime batting average was .311, and he led the Dodgers to six league championships and one World Series victory.

After retiring from baseball early in 1957, Robinson became involved in business and in civil rights activism. He was a spokesperson for the National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and made appearances with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

With his induction in 1962, Robinson became the first Black person in the Baseball Hall of Fame, in Cooperstown, New York.

His autobiography, I Never Had It Made, was published in 1972.

In his powerful autobiography he bluntly writes:

“I cannot possibly believe I have it made while so many of my black brothers and sisters are hungry, inadequately housed, insufficiently clothed, denied their dignity as they live in slums or barely exist on welfare,’’ Robinson wrote. “I cannot say I have it made while our country drives full speed ahead to deeper rifts between men and women of varying colors, speeds along a course toward more and more racism.’’

In another chapter of the book, Robinson talks about Freedom Bank, the Black-owned, black-operated bank in Harlem Robinson helped open in the 1960s.

“During the post-baseball years, I became increasingly persuaded that there were two keys to the advancement of blacks in America — the ballot and the buck.’’

The autobiography was released four days after his death on October 24, 1972, from a heart attack, with underlying diabetes and associated complications. He was 53.

In 1984 Robinson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor for an American civilian.

Exactly 50 years after he broke the color barrier, on April 15, 1997, Robinson’s career was honored as his uniform number, 42, was retired from Major League Baseball by Commissioner Bud Selig at a ceremony at New York’s Shea Stadium.

On April 15th, players, coaches and managers throughout Major League Baseball will play a special tribute video that will air at every ballpark and continue the annual tradition of wearing Robinson’s iconic No. 42. This year to celebrate the 75th anniversary, all the 42s will be colored Dodger Blue, regardless of a team’s primary colors.

On July 19, the Dodgers will host the All-Star game and the Robinson-related tributes will continue as his widow, Rachel turns 100 that day.

Irv Randolph is an award-winning journalist and political commentator. The Randolph Report is a weekly newsletter on politics, culture and career and professional development relevant to African Americans. Subscribe for free and get the latest articles sent directly to your inbox.